Last spring, some colleagues and I began a gardening group in the grounds of our workplace growing potatoes, onions, squash and a little bit of everything else we fancied. Some of us were completely clueless (myself included – I entered into the lunchtime activities armed only with an iPhone app) while others already knew a fair amount about the art of ‘growing your own’. The group has developed and prospered, and a year later we are digging a further bed, allocating vegetables to people and looking out for an extra water butt (nb if you’re Norwich based and you can help, let me know!)

I’ve recently come across Norfolk market gardeners in my own family tree, and spotted several listed in trade directories in villages I’ve been doing research on. For this blog, I thought I’d delve into the history of the industry locally in the hope that it may be of interest to others.

While different to modern day land shares and community groups through their commercial nature, employees of market gardens of another age were nevertheless using many of the same skills as modern day gardeners – and doing so far better than many of us. I’m sure I’m not alone in wishing to see a return to more localised, seasonal and organic farming, and it would be wonderful to ensure that the East Anglian market garden heritage and skills aren’t completely lost to history.

A ‘market garden’ was historically a term for farming aimed at producing vegetables and berries, rather than grain, dairy or orchards; in other words farming by the hoe, not the plough. Although the word ‘garden’ may suggest a small set up, this was not always the case. Most gardens, especially towards the beginning of their rise to prominence, were necessarily located close to their markets. Those of the mid 1800s were growing all kinds of produce for local consumption and, by the time of the expansion of the railways, urban areas much further away.

Great Plumstead (arguably meaning ‘dwelling place near plums’) was one of many Norfolk villages to boast successful market gardens – other locations included Mulbarton and Bracon Ash. All three were within striking distance of regular markets in Norwich. In Suffolk*, one of the most wellknown villages for market gardening was Belton, and the recent discovery of market gardener and grave digger Richard Pole’s diaries (see article here) has reawakened interest in an industry which boomed with the railways and the need to feed an ever-growing population. Richard’s diaries describe growing wheat, barley, potatoes, beet, turnips, peas, lettuce, asparagus, rhubarb, strawberries, gooseberries and other fruit….showing just how varied the produce of a market garden could be. Richard, like others in Belton and villages like Filby, further north, were able to sell their produce in Great Yarmouth and later export their goods by train to London. A hundred years after the surge in market gardening took hold, the industry started to decline. The end of the Second World War brought foreign imports into the country and the growing move towards largescale monoculture encroached on previously market garden dominated areas.

(*I should note that Belton was part of Suffolk until 1974, when the border moved and it became part of Norfolk.)

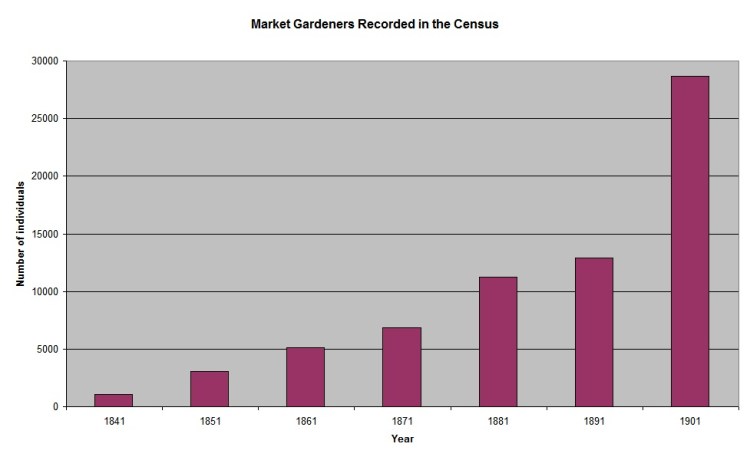

A key word search in the census for ‘market gardener’ reveals the growth of this type of farming as an occupation across the country during Victoria’s reign. About a thousand were recorded in 1841. This figured tripled over the next decade, and almost doubled again over the next (by 1861 there were 5100). The total more than doubled all over again during the next twenty years to 1881. By 1901, a total of 28,700 individuals were employed as market gardeners – and those are only the ones captured by the census.

Somewhat entertainingly, several of the men recorded also had the surname ‘Gardener’!

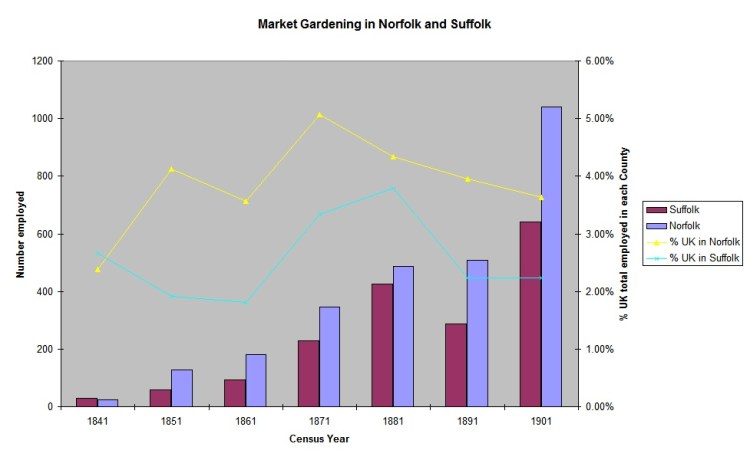

On a more local basis, Suffolk, and particularly Norfolk, were strong market gardening counties. Then, as now, being known for their agricultural produce.

During the middle of the Victorian period, Norfolk contributed a little over 5% of the Country’s market gardeners, and Suffolk was about 1.5% behind its neighbour. Based on Norfolk’s population, market gardening rose from the occupation of less than one in every ten thousand people in 1841 to one in every 500 by 1901. In Suffolk, proportions were roughly half that recorded in Norfolk.

The 1908 map of Norwich South shows acres of Allotment Gardens which are today underneath modern-day developments. Nowadays, the local council has a waiting list chock-a-block with local people wanting to get hold of a piece of land – and what some of them wouldn’t give to have that growing space back!

So many of my blogs have shown just how much history repeats itself – not least where it comes to corsets, first names and vegetables in recent times! As we strive to cut carbon emissions, know more about where our food comes from and support the local economy, we are (hopefully) beginning to learn from the past while moving forward into the future. The tide appears to be turning on some of the processes which we once called ‘progress’ and we are perhaps beginning to appreciate how much better some of our forebears may have understood the environment that we live in.

It seems quite right that the Bracondale Gardeners (perhaps soon the Knucklebone Gardeners – but that will need the honour of its own post!) are making the most of a patch of land which was once in the middle of a thriving market gardening area. Hopefully we will soon be proving that we can produce just as many fabulous vegetables as the original Lakenham vegetable growers. One thing is for certain though. None of the fruits of our labours will find themselves on the train for London’s markets. If last year is anything to go by, they’ll be enjoyed much closer to home!