For week two of #52Ancestors, we’re urged to record a favourite find. Well, here’s one of mine. It comes with an explanation of what I think might have happened, some canine facts, and a couple of tips for archive visits.

My favourite will (…maybe, there are lots of contenders)

Daniel Spalding, Brockdish, 1733-35. ANF, will register, 1731-1737, fo. 116, (1733-1735, no. 28). Repository: Norfolk Record Office.

(28)

In the Name of God Amen I

Daniel Spalding of Brockdish in the County of Norf[olk] Gent[leman]

Doe make th[i]s my last Will and Tes[tamen]t revoking all ot[he]r Wills by me

made heretofore made It[e]m I give and devise unto Joshua Nelson of

Bungay in the County of Norf[olk*] Attorney the Sum of Two hundred

pounds and to his Sister the Widow Bransby the Sum of Two hundred

pounds and to Rob[er]t Nelson the Barber the Sum of Forty pounds and unto

Daniel Nelson in the County of Norf[olk] Surgeon the Sum of Two hundred

pounds provided he keep and maintaine tenn Couples of my best Otter

doges Item I give unt[o] [?] the son of M[iste]r Goddard the

The House and Hemplands late the Estate purchased

of M[iste]r Palgrave //

…and that’s it!!!

*in the original copy, this has been crossed out and replaced with ‘Suff’; this transcription is from the registered copy, which isn’t the one pictured below.

Who was Daniel Spalding, and what happened to him?

This question is more fully answered in The Moated Grange by Elaine Murphy. It was through early research surrounding the 18th century occupants of the Grange that I found Daniel’s will (initially the registered copy) on microfilm in the Norfolk Record Office searchroom back in 2012 or thereabouts.

Daniel was born in 1666. From the limited information we have, he appears to have been a country gentleman, interested primarily in country pursuits – perhaps otter hunting especially based on remaining evidence. Daniel was well off by local standards and could apparently afford to enjoy himself. When his grandfather died, Daniel was only a little boy. He was left a collection of law books with a suggestion that he might one day become a lawyer.

His grandfather’s dying wish does not appear to have been granted. When Daniel crops up in newspapers, it is almost invariably connected to otter hunting and horseracing. A lifelong bachelor, he lived in Brockdish (as far as we know) throughout his life. Whether or not the newspaper articles accurately reflect his life as a whole is difficult to say. Only some topics make newsprint, and the pieces we’ve found so far reflect just days – hours – from a life of more than six decades.

Coming back to his will, we have to wonder why it is so short. When I first found it, I imagined a young man falling from his horse, perhaps leaping a ditch mid chase, before being carried back to his home. There, maybe he started to dictate his final wishes, expiring before he got further than a couple of bequests to friends and the safekeeping of his dogs…

There are other possibilities, of course. The above may not stand up to scrutiny as Daniel may well have started penning the will himself. He was also much older at death than I initially realised. (Far be it for me to suggest he couldn’t have been competing in a steeplechase in his 60s, but those days may have been behind him?). Perhaps he was sick but did not consider making a will until it was too late to complete it. Perhaps his sickness was sudden onset.

Indeed, this may not be a deathbed will at all. He could have started writing it years before his death, but having no wife or children thought it wasn’t a priority. His sister (who lived with him after she lost her husband) would inherit all anyway if his will did not meet requirements, so why bother? Maybe Daniel didn’t want to think about his death at all until it was too late, or his sister walked in on him as he was writing and gave him short shrift about his wishes. Perhaps he started writing it at a card game, in debt to his friends and the worse for drink, the document discarded in a drawer until it was found at his death. Who knows.

Whatever happened, it’s interesting to mull over Daniel’s priorities when it was written. He remembered the Nelsons with rich bequests. Were they friends from the hunting field or more than that? I wonder if Daniel Nelson, Surgeon, really did take on ten couple of Daniel’s otter dogs for the grand sum of £200 (if Daniel even still had them when he died)? Did Daniel prize his otter dogs as companions, even pets, or strictly for catching otters and the ‘sport’ it provided?

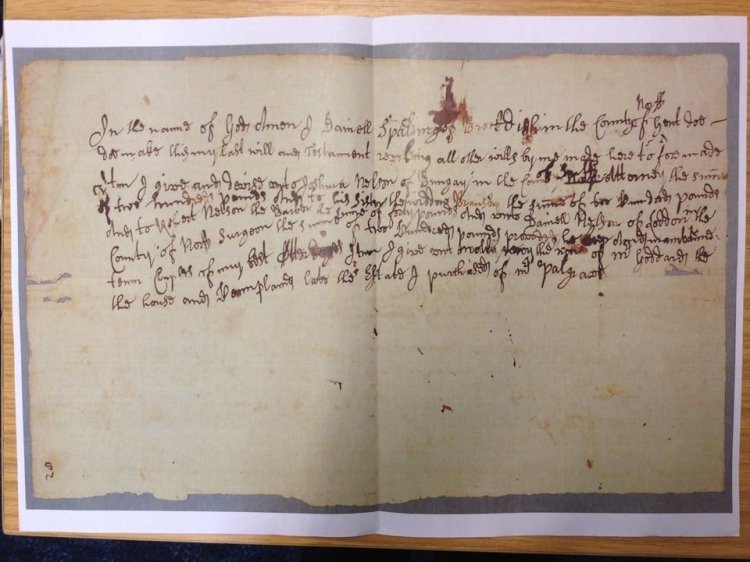

It may be one short document, but holding the original will was quite an experience. A jumbled note from 300 years ago that somehow speaks more than its few words. I am so glad that the searchroom assistant suggested ordering the original from the strongroom just in case the registered copy wasn’t the whole record. Take a look at the picture below. I know you can’t hold it yourself, but it’s evocative, no? How many people had held it between me in 2012 and Daniel (or his scribe) in the 1700s? Perhaps he could have died clasping his pen after writing that last word after all…

Daniel was buried at Brockdish on 25 July 1733.

What is the difference between a registered copy and an original will?

Registered copies are versions of the original written up by clerks into volumes containing lots of wills (once a court had proved them). When you look at wills online, you often look at registered copies, sometimes digitised from microfilm created several years ago. It’s not always the case; some more recent digitisation projects have used colour images of original wills (see below!)

Original wills come in all shapes and sizes and may survive in addition to registered copies. They are often only produced in ‘real life’ under exceptional circumstances. For example, in their research guide, the Norfolk Record Office states that you might view an original if there is ‘no registered copy or to compare a signature’. In the case of Daniel Spalding, the registered copy of the will seemed unfinished for some reason. It turned out, of course, that so was the original – not the fault of the clerk at all!

What is an Otter Dog? A brief history

The clue is in the name. In earlier centuries, Otter Dogs (or Otterhounds as we would say today) were used for hunting otters through water and mud. Otter hunting has been banned for more than forty years – otters were rightly given legal protection in 1978 due to falling numbers. Otterhounds are no longer very common; the Kennel Club now considers them a Vulnerable Native Breed. They are large dogs, probably with French and English ancestry, sporting a thick, weather-resistant oily coat. Otterhounds have webbed feet and excellent scenting ability together with great strength and stamina and a long stride.

That said, in Daniel Spalding’s time, otter dogs may have looked a little different to those we recognise today. As a distinct breed, they only date back to the early 1800s.

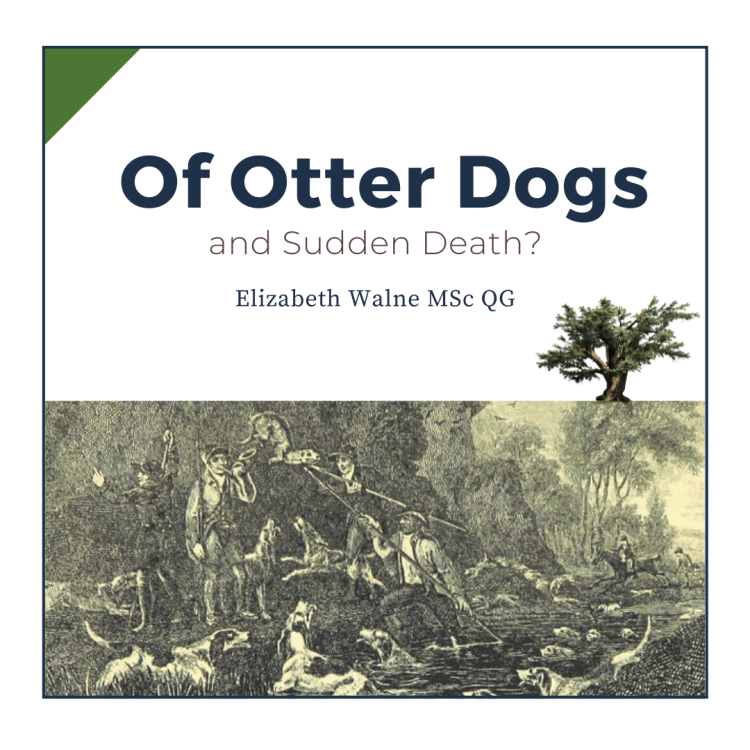

“Otter Hunting” from Somerville’s Chase, 1886, page 143, held at the British Library. Author William Somerville, 1675-1742 (a similar period to Daniel Spalding). Image made available on the British Library’s Flickr page, no known copyright restrictions.

Two top tips for visiting the archives inspired by this post

1. If the registered will is odd somehow, find out if an original survives and if you might be able to access it. The answer might be ‘no’, but at least you’ve asked the question, and you could be richly rewarded.

2. If you have a question at an archive, ask. The searchroom assistant suggested I order up the original will in this case, and even if there were no more words on the record, the document told a story in other ways. Record Office staff are knowledgeable and, if I dare say, increasingly treated as expendable by budget keepers. We need our experienced archive and heritage staff, and if we don’t acknowledge their skills, thank them and recognise them, then there’s a danger even more of them will be cut from our searchrooms, libraries and museums. [*Gets down from soapbox*]